…It was on the second day in the month of Adar in the year 5340 of Creation (A.D. 1580) that the momentous event took place. At four in the morning, the three made their way out of the city to the river Moldau. There, on the clay bank of the river, they moulded the figure of a man three ells in length. They fashioned for him, hands and feet and a head, and drew his features in clear human relief…

The Golem of Prague, Rabbi Yehuda Loew

The slender silhouettes created by Alberto Giacometti are a compelling recreation of a primitive cosmogony and perhaps an interrogation of our place within its realms. The totemic figures seem to emanate from the seminal magma as if lava outpourings had instantly chilled at the contact with air. These golems are thus trapped in various positions: some are stoically standing, others are caught in the process of walking as if they would defy their status. They bring to our mind the works crafted by the Dogon culture in Africa, which are also imbued with the matrix of movement: with flexed knees, they threaten to jump at the spectator, a reminder of their dual citizenship. A rare meeting of wood and life…

But where is this man going? To me, he speaks loudly about the motoric force of human endeavours.

L'homme qui marche, 1960. Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti. Paris, inv.1994-0186. © Succession Giacometti/SAVA, 2012

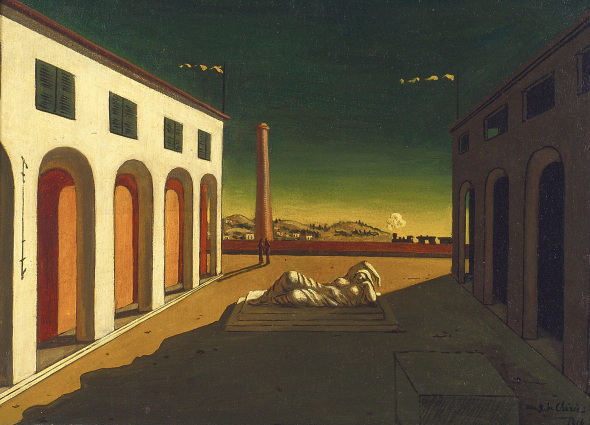

Giacometti’s figures are deeply rooted in the ground, by prominent feet which sometimes fuse to form a sort of pedestal. Matter, in his hands, has been thinned to such a critical state that it can barely suffice to host the last corner where humanity dwells. These dramatically stretched figures, suffused with the melancholy of a bygone world, distil mystery that captures the viewer’s attention. We could easily imagine them taking a stroll and projecting their long shadows at sunset in one of the enigmatic piazze proposed by Giorgio De Chirico.

The Menil Collection, Houston

Photo: Hickey-Robertson, Houston.

Due to their magic summoning power, these creatures may remind us of the period spent by Max Ernst in the American West. His “Capricorne” group dating from 1947 might be a perfect rendition of a royal couple dressed in full regalia, presiding over a court somewhere in the Pacific (1).

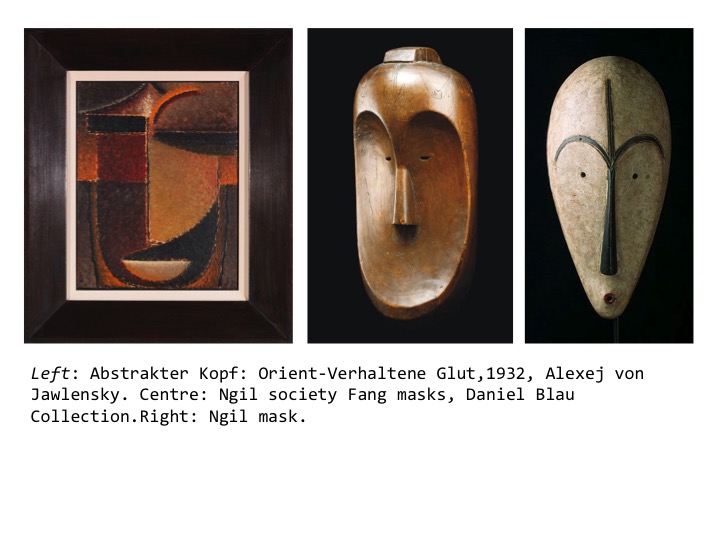

Incursions into non-Western art at the beginning of the XXth century were numerous. Fueled by a quest for the yet unseen, a search for a forest of virgin images, artists like Picasso, Derain and Modigliani ventured in this direction. A geometrising view of the human face characterised “Abstract Head” painted by Alexander von Jawlensky in 1932. We can find traces of a similar reductionist procedure in some masks from the Ngil secret society, crafted by the Fang culture in Gabon (2).

Giacometti’s sculptures may also bring to our mind the elongated and graceful grade figures created in the Banks Islands, in northern Vanuatu (3, 4).

These images represent potent ancestors and were usually displayed at the façades of ceremonial houses, reminding us that individuals in those societies were embedded in a symbolically complex network, ruled by ancestry and lineage (4). Could Giacometti’s effigies have been created in the same spirit?

What motivates us to paint or sculpt faces in so many possible ways? Across the centuries and in various cultures, these motivations differed enormously. Be it a dignified portrait of a wealthy banker in Renaissance Tuscany or the African masks used in specific rituals, all these images form an inexhaustible repository of everything that makes us humans. Are there any specific systems in our brain that deal with the perception of faces? We will later discuss our strange fascination with the human body and faces, focusing on the role played by the inferotemporal cortex in face recognition. How do face recognition systems work? But that’s Zukunftsmusik…

Perhaps all these images are variations of a single identity, a map of ourselves that we constantly need to update, a system of references used to navigate. Maybe these faces contain a solution, as suggested by Jorge Luis Borges in the Epilogue to Dreamtigers:

A man sets himself the task of portraying the world. Through the years he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and people. Shortly before his death, he discovers that that patient labyrinth of lines traces the image of his face. (From Dreamtigers, written by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Harold Morland from the original in Spanish “El Hacedor”, published in 1960).

References

- Max Ernst, Dream and Revolution, Text by Werner Spiess & Iris Müller-Westermann. Hatje Cantz

Publisher, 2008. - African Masks, Franco Monti, 1969.

- Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Eric Kjellgren, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007.

- The Pacific Arts of Polynesia and Micronesia, Adrienne Kaeppler, Oxford University Press, 2008.