As we saw in a previous article, the prologue of Baroque French operas provided a suitable format for celebrating the sovereign and perpetuating its glory. The effectiveness of this form of power representation relied on visual spectacle to support the narrative of the king’s exploits. In the long term, however, as a performing art, opera’s potential to praise the king’s government and contribute to his subjects’ collective memory was limited compared with the visual arts, epic poetry, or architecture. All arts were thus evaluated in terms of their ability to glorify the king and generate an enduring image of his acts of government.

In practice, the aim was to reconcile two difficult-to-harmonise requirements. On the one hand, the pretension of artists and thinkers close to the king was to exalt the dimension of his politico-military enterprises, for which no human measure seemed sufficient. To give a full account of his triumphs, it seemed necessary to resort to the divine order. However, this program initially did not seek to explicitly equate the monarch with the heroes or gods of Antiquity. Instead, allegory was privileged for its power to encode hidden meanings through symbols. On the other hand, the recipient of this encrypted message still had to be able to decode it and tie up the ends correctly. The challenge, therefore, consisted in balancing these supposedly contradictory requirements: symbolic abstraction and comprehensibility.

Painting & tapestry

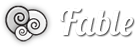

Charles Le Brun[1] chose an allegory to decorate the Grand Appartement at Versailles between 1671 and 1681. This series of seven adjoining rooms was intended to serve as an impressive setting for the sovereign’s official acts. In this appartement de parade, ambassadors were led through rooms of increasing opulence as they approached the monarch. When he decorated this space, Le Brun was mindful of not offending the sensibilities of high foreign dignitaries while, at the same time, paying tribute to Louis XIV. In a gradient from mythology to history, the paintings in these rooms depict the exploits of Alexander the Great and Augustus and tacitly suggest the French monarch as someone worthy of rubbing elbows with them. Although the Sun King himself is not portrayed, his association with the heroes and deities of the past was expected to be completed in the beholder’s mind. A similar approach was adopted by Le Brun for his series of tapestries based on the triumphs of Alexander the Great, now on display at the Louvre Museum.[2]

The entry of Alexander into Babylon, about 1665, probably by 1676. After a design by Charles Le Brun (1619-1690). Woven by the Gobelins Manufactory. Wool, silk, gilt metal and silver-wrapped thread. Le Mobilier National.

His next project, however, marked a change of strategy. The design and construction of the Ambassadors’ Staircase at Versailles kept him busy between 1674 and 1678. This staircase, profusely decorated with paintings on its ceiling and walls, was to lead foreign envoys to the king’s public apartments and thus served a function similar to that of the parade rooms. Here, in contrast to the Grand Appartement, Louis himself is depicted directly in the company of several allegorical figures. Le Brun chose to combine poetic references with events from the king’s history so that each would serve as a support for the other, as suggested by L. C. Le Fèvre in 1725 when he said that “allegorical symbols lose their force if they degenerate into pure poetic imaginings that are not accompanied by sufficient evidence”.[3]

In 1678 there was a change in the official policy of power representation. After the treaty of Nijmegen by which France obtained the Franche-Comté from Spain, Le Brun began to prepare a new and ambitious pictorial cycle to decorate the ceiling of the Grande Galerie, today known as the Gallery of Mirrors. The original plans included reminiscences of Hercules and Apollo. However, after the new territorial gains, Louis XIV expressed his wish to appear in scenes portraying his military triumphs. Therefore, Le Brun was instructed to respect precise time boundaries in his representation of heroism’s chronology: the cycle should start in 1661-the year Louis took control of the government after Mazarin’s death- and conclude with his most recent campaign. In these paintings, Louis XIV replaces Hercules and Apollo and appears wearing the garb of the ancient Roman generals.

This scene actually had been staged in 1662 when Louis XIV impersonated the head of the Roman quadrille, in the guise of a Roman emperor, during the Carrousel festivities attended by 15000 spectators. The motto UT VIDI VICI (As soon as I saw, I conquered) shone on his coat of arms, which included a device portraying a rising sun that confidently pushed away all clouds during his irresistible ascent. That day, the festival’s participants witnessed the birth of Louis’ solar mythology.

A few years later, Le Brun’s approach would use allegory as a unifying element to bring together the earthly and the divine, history and myth, to leap temporal barriers and generate a new mythico-historical narrative outside of time.

Poetry and historiography

Concerns about correctly calibrating representation modes of the king’s power were not new; before Le Brun, the members of the Petite Académie, founded in 1663, discussed the appropriateness of using medals, sculptures or paintings to celebrate the Sun King. This group, which included Charles Perrault and Jean Chapelain, among other prominent intellectuals, aimed to find an enduring strategy for the politics of encomium. Chapelain put forward the use of gold and silver medals, likely to stand the test of time. He also considered narrative poetry a suitable instrument; however, he was concerned that its fabulous nature and its propensity for exaggeration could undermine the message’s credibility. Epic poetry ran the risk of readers seeing the king and his heroic deeds as fiction.

Writing a monumental history of Louis’ reign was also seen as an option, but in the end, discarded because of the fear of exposing state secrets. Finally, the scale seemed to tip in favour of the panegyric genre, at least as a temporary solution. Chapelain viewed Le Brun’s pictorial efforts with scepticism and reminded his colleagues at the Petite Académie that painting was not as long-lived as poetry. On the other hand, the complex allegorical language in which events from recent and remote history mingle with mythology represented a self-contained universe that was difficult to access. Even explanatory guides were published to facilitate their interpretation! Thus one of these writers expounded the meaning of a scene where the king appeared in control of a rudder by saying that “it shows that His Majesty is now in control of the government”.[4]

Opera

Downing Thomas postulates that the prologues of the tragédies lyriques may have become a more effective tool than the visual arts for constructing the future memory of the reign. As in the ceiling of the Grande Galerie, the hybridisation of historical events transplanted from distant chronologies with mythological elements ended up dislocating the time-space coordinates to place the monarch outside of any known paragon, as if preserved for posterity in amber. This search for temporality is clearly seen in the prologue of Lully’s opera Atys(1676). In this piece, the arrival of a new hero, surpassing all precedents, makes Time pause proceedings.[5] Unlike the participation of Louis in ballet performances-he appeared for the last time on stage during the performance of Ballet de Flore in 1669-the operas conceived by Lully and Quinault concealed the king and replaced him with a network of veiled associations born of the divergence between what was suggested and what was shown. However, even as a tacit reference, he was this homage’s ultimate addressee: spectator, benefactor and tutelary figure of the operatic prologues. Opera thus met several of the requirements defined by the Petite Académie. As the heir to classical tragedy, it stood on a poetic core but at the same time served as a powerful panegyric. If we agree with Racine that “panegyrics and history are as distant from each other as the heavens are from the earth,”[6] then what other form of representation could be more vigorous in giving birth to a new collective memory?

Sculpture and architecture

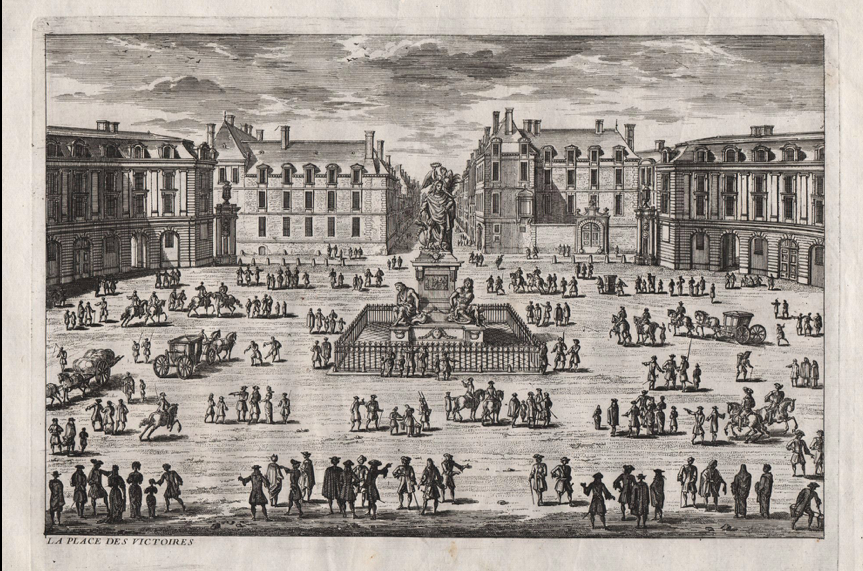

In the past, equestrian statues modelled after the heroes of Antiquity were powerful symbols celebrating the ruler. Both in scale and materials, they were made to last and be seen. They would represent a physical effigy of the sovereign vis-à-vis his subjects, especially in urban settings. When Louis XIV decided to leave the capital and establish his court at Versailles, an ambitious urban plan to honour him came into operation. Since his disappearance from the stage, Louis started being more conspicuous than ever in French opera through indirect allusions; similarly, after his move to Versailles in 1682, he sought to perpetuate his memory in Paris by commissioning the construction of royal squares (places royales). These were regular, ordered open spaces specifically created to accommodate a monumental statue of the monarch in their centre, with the peculiarity that both the architecture backdrop and the statue were built simultaneously and complemented each other in aesthetic appearance and political significance.[7] The prototype of such a royal square was the Place des Victoires, inaugurated in 1684 and built under the auspices of François d’Aubusson de La Feuillade, who gave the impetus to celebrate the victories of the Sun King in the Franco-Dutch War. Royal squares soon proved to be effective for the glorification of the king and flourished throughout the kingdom. The Marquis de Louvois, Secretary of State for War and Superintendent of Buildings, was convinced by the project of de la Feuillade and began, at the time of the work on the Place des Victoires, to plan a much larger royal square for the capital: the Place Vendôme, which was first called the Place de Nos Conquêtes or the Place Louis-le-Grand. From 1684 onwards, many such projects were submitted to the king for authorisation.

La Place des Victoires. Adam Pérelle, engraver

Jean Mariette, publisher. Around 1660. Carnavalet Museum, History of Paris. G.13360

Versailles

The Palace of Versailles is a compelling testament to his solar inspiration: the central axis of its gardens starts from the main building and disappears into infinity in a vanishing point framed by two groves called “The Pillars of Hercules”. The sun rises behind the building and sets at that distant point where infinity meets the horizon, delineating a celestial trajectory that represents the king. Just as Louis had already been symbolically identified with the heroes of Antiquity in operas and paintings, the topographical arrangement of the gardens paid him a final homage as a solar divinity, integrating him into the symbolic structure of the park.[8] Absence may be a powerful version of eloquence.

***

To conclude, we saw that the reign of Louis XIV was marked by significant contributions to the arts, which served an ambitious political agenda under centralised management. The king’s absolute power was projected to all domains of human creativity. This article focused on how the arts were employed to push forward this glorification programme. Their potential contribution to commemorating the sovereign was carefully considered in the light of Paragone-like arguments. It remains for us to explore how this policy of encomium also impacted the flowering of the sciences under the Sun King, but that will be the focus of a future article.

References

[1] Charles Le Brun (1619-1690) was a French painter, architect, and draftsman who also directed the Gobelin Manufactory. He served as rector and chancellor of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture and led the work on the decoration of the palaces of Vaux-le-Vicomte and Versailles. He was one of the most important and influential artists of the Louis XIV style.

[2] Downing Thomas, Aesthetics of opera in the Ancien Régime, 1647-1785 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p.55.

[3] Ibid. p.61.

[4] Ibid. p.70.

[5] Ibid. p.82.

[6] Ibid. p.68.

[7] Ziegler, H (2002) L’invention des places royales. In Sarmant, T & Gaume L, (editors) : La place Vendôme. Art, pouvoir et fortune. Paris 2002, pp 32-41.

[8] Weiss, A (2011) Miroirs de l’infini. Le jardin à la française et la métaphysique au 17éme siècle. Paris, Éditions du Seuil, p.72.