In his poem “Time, Real and Imaginary” the English writer Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) tells us about an endless race between two kids: a little girl and her blind brother. The girl is taking the lead, but at some point, she looks over her shoulders just to find her brother struggling to catch up. This poem suggests that our imagination flies ahead, transporting us to the realm where everything is possible. On the contrary, our senses anchor us to the present, binding us to the immediate circumstances.

This work introduces two substantially different ways of perceiving time. The blind boy symbolizes the metric time that marks the beat of our everyday lives while being unaware of the future and what it will bring to us. But we also have the imaginary time represented by the girl, the time of our expectations, dreams, and plans that defy any measuring system. Unfortunately, more often than we would like, we see that little girl mischievously waving at us from a distance! We seem to uncomfortably dwell in this intertidal zone, too eager to accomplish our plans and dreams, anxious to push them to the past and always prepared to run after new goals.

Coleridge was a Romantic poet, and Romanticism was, in many ways, a counter-reaction to the Enlightenment. After a century dominated by reason and logic, things loosened up a bit. Communicating our emotions and subjective feelings became necessary, and poets and painters began to sing the passing of time, unattainable love, and the intrinsic beauty of nature. Lover’s urgent letters and epic sunsets populate the paintings and books from this period.

But long before the Romantics swept the stage, artists were already reflecting on the passing of time and our limited experience as human beings. We will now consider a few examples, starting in the XVIIth century and moving chronologically to include contemporary answers to this problem. On our next entry, we will discuss current research on time perception in the human brain. Do we actually perceive time or rather events changing during the time?

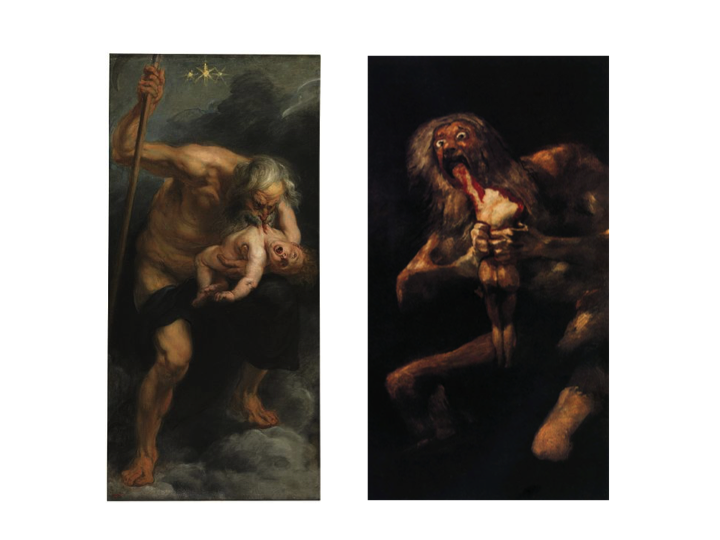

Rubens and Goya

If you ever doubted that time could efficiently dismantle your plans, then these two paintings will convince you of the contrary. When considering a given problem, sometimes we find an unexpected ally in etymology. For instance, in French, the word for “time-consuming” is chronophage (from the Greek chronos ‘time’ and phagos ‘eater’). Time’s tyranny is nowhere as vividly expressed in visual terms as in these two paintings by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Francisco de Goya (1746-1828).

Saturn devouring his sons, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid. On the left, Rubens’ version of the mythological scene. On the right, Goya’s treatment of the same subject.

In pre-Socratic Greece, Chronos was the Greek God of Time (later Romanized as Saturn), and since then, he was frequently represented as a destructive force. In his Theogony, Hesiod gives an articulated version of several Greek myths that explain the beginning of the universe. We learn that Chronos gained control over the Cosmos, but he felt threatened by a prophecy announcing that one of his sons would overthrow him, just as he did with his father. To avoid this, he devoured his children: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. However, Zeus was spared and realized the prophecy. This allegory is explicit enough for us to associate our expectations and desires (that develop in a plane of potentiality, in a yet unwound future) with Chronos’ progeny, which incarnates the wishes of renewal that thrive in youth.

Both painters depict Chronos (Saturn) as an older adult, but that’s where the similarities end; their takes on the mythological scene are drastically different. While Rubens adopts a more conventional approach in tune with the Baroque spirit, Goya disturbs us with an image of extreme ferocity. Cultivating his penchant for the bizarre and fantastic, Goya recreated the moment when Saturn feasts on his son in a cannibalistic frenzy. He probably painted this scene during his last years, and we can perhaps ascribe this dark imagery to his weak condition and the feeling of impending death. Saturn was also frequently associated with melancholy. This view stemmed from the ancient doctrine of temperaments, which believed in the astrological influence on body fluids and its impact on the mood of a person. Contrary to its medieval connotations, when melancholy was considered a pathological state, it was glorified during the Renaissance as the precondition of genius and inspiration. Alternatively, other explanations for this painting include possible links with the adverse Spanish political context of the time.

The Dutch Golden Age and vanitas paintings

In the XVIIth century, the Dutch Republic was an enclave of economic prosperity and civic freedom. Boasting a powerful fleet and commercial outposts in Europe, Asia, and America, it was a young and wealthy state governed by citizens, as opposed to neighboring nations ruled by kings. Trade was the base of the economy, and work opportunities attracted artisans, artists, and intellectuals who settled in cities like Haarlem, Delft, Leiden, and Amsterdam. During this period, which was later called the Golden Age, the arts flourished, in particular, painting. Artists catered to a burgeoning middle-class, avid to validate their newly-acquired social status through the collection of works of art. It was hard to satiate this expanding market, and competition between painters led to their specialization. Many artists only focused on the production of vanitas paintings, like the one shown here, by the Dutch artist Hendrick Andriessen (1607-1655).

Vanitas still-life with a mask, Hendrick Andriessen. The Daisy Linda Ward Collection, The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

In the vanitas genre, painters used a variety of symbols to convey a clear message to the viewer: the knowledge of the world and all its riches are temporary, following the biblical precept Vanitas Vanitatum, Omnia Vanitas, all is vanity (from Ecclesiastes). The watch with a blue ribbon on the left indicates the passage of time. Death alluded to by the skull on the table makes earthly pleasures like lavish guilt cups, books, and musical instruments superfluous. The soap bubbles and the taper used to light tobacco, as well as the flowers, are all direct references to the transience of life. In the predominantly Protestant Dutch Republic, these images were powerful reminders of temperance and aimed at discouraging self-indulgence, embracing austerity as a means of living religiosity.

On Kawara and Roman Opałka: time series

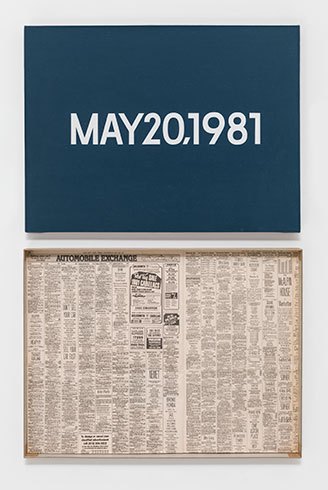

On Kawara (1932-2014) was a Japanese conceptual artist whose work explores the passing of time and its traces. In the series called Today, each painting merely consists of the work’s date of creation, hand-written with exquisite precision in white letters on a variably colored background. He would usually document time in the local language of the country where he was working. Not every day of the year attracted his attention, but he sometimes produced two or three paintings in a single day. If a piece of work was not ready by midnight, he discarded it. Each work came in a cardboard box crafted by the artist and lined with local newspaper clippings from that particular day.

On Kawara, MAY 20, 1981 (“Wednesday.”). New York. From Today, 1966–2013. Acrylic on canvas. Pictured with an artist-made cardboard storage box Private collection. © On Kawara. Photo: Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

A date laconically summarizes the daily richness in the life of an individual or the entire humanity. Different time points and production places converge on a unique and ascetic presentation mode: a rectangular area bearing an inscription in white Futura typeset lettering. However, these paintings also map the differences in language and geography and suggest that cultural traits might also be ingredients of the subjective experience of time.

In One Million Years, two narrators list each year in a one-million-year period elapsed from the date of creation of the work (1969, the year when humans landed on the Moon) and the million years that preceded it. The sprawling scope of this work captures the vastness of time by offering an abridged version of it. Each year is compressed in the time scale, lasting only for a few seconds, just the time it takes to read a number. The work becomes an index of time, a sort of litany where numbers orally pile up, revealing a never-ending series. This work will be recreated during the Venice Biennale 2017, and volunteers are needed!

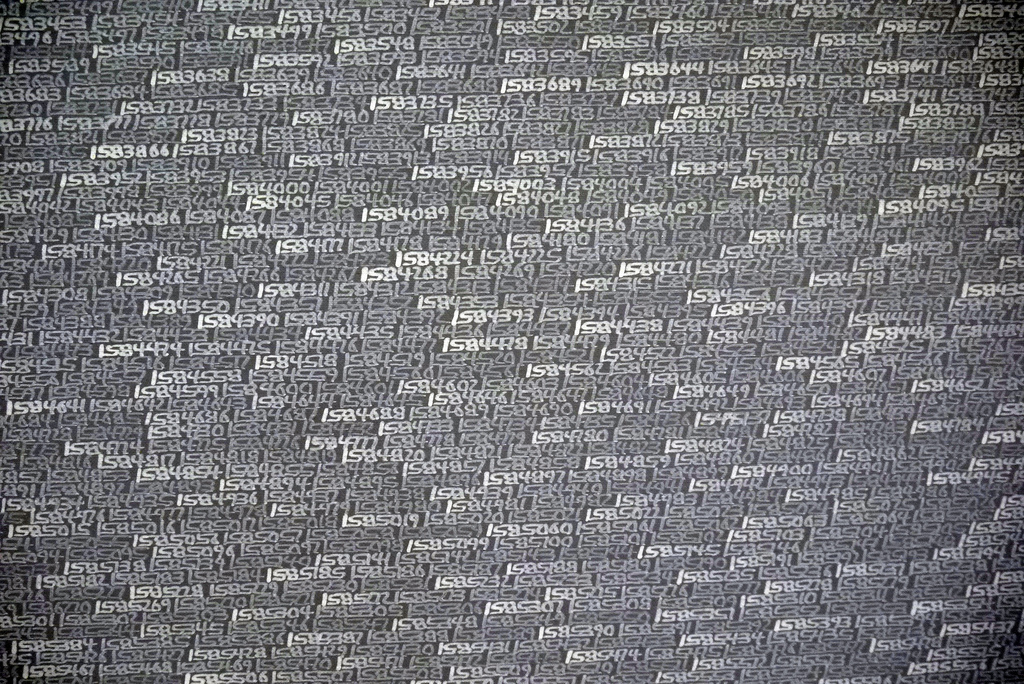

Roman Opałka (1931-2011) was a Polish artist that shared with On Kawara a keen interest in number series and the exploration of time perception. His life revolved around a central artistic project called 1965 / 1 – ∞. In 1965 he began to painstakingly annotate numbers from one to infinity, always starting in the top left-hand corner of the canvas. Once the surface was used up, he would continue painting on a new one. He completed his work on August 6th, 2011, reaching the number 5607249. The scope of this project tried to put into perspective the dimension of temporality and the scale of human endeavors, stressing the temporal content inherent to number series. His lifelong reflection on time was in itself an ongoing artistic project animated by a focus on mathematics, or as he put it, ¨the finite defined by the nonfinite¨.

Roman Opałka, 1965 / 1 – ∞

Christian Marclay

In The Clock, Christian Marclay (1955) assembled a 24 hr photomontage of films and television clips showing people that look at their watches. Marclay spent two years splicing small bits extracted from footage comprising everything from famous movies to tv advertisements. The visual installation unfolds like a fast-paced movie. Still, there is something quite remarkable about it: at any given moment, the real time coincides with that shown on the video excerpts, with the accuracy of a chronometer. Marclay creates a modern vanitas that prompts the viewer to question our vital urgency in the contemporary world. Like the fictional characters in the film, who constantly check the time, we can reflect on how we make use of this precious commodity.

QUOTES

Time, Real and Imaginary.

ON the wide level of a mountain’s head

(I knew not where, but ’twas some faery place),

Their pinions, ostrich-like, for sails outspread,

Two lovely children run an endless race,

A sister and a brother!

This far outstripp’d the other;

Yet ever runs she with reverted face,

And looks and listens for the boy behind:

For he, alas! is blind!

O’er rough and smooth with even step he pass’d,

And knows not whether he be first or last.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

References

Meijer F.G. (2003) Dutch and Flemish Still-Life Paintings bequeathed by Daisy Linda Ward, The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Waanders Publishers, Zwolle, 2003.

https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5?locale=en

http://i-ac.eu/fr/artistes/81_on-kawara