“Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis faciebat anno 1666”, reads the signature on the first of a famous series of string instruments that would become legendary. Between the “Sunrise” violin from 1677 and his last work, the aptly named “Chant du cygne” (Swansong) from 1737, Stradivari produced around one thousand and one hundred instruments. From this rich legacy, about six hundred have survived to the present day in the hands of musicians and collectors or locked in the safety vaults of investors. Many more could be merely slumbering in their cases, unbothered by the passing of time.

Forgotten in taxicabs, stolen, resurfaced in night-clubs or confiscated by the Nazis, these instruments secured for themselves a leading role in a long and outlandish saga. The changing hands through which they passed, recorded in the evocative names with which they conquer auctions (for instance, the “Lady Blunt” from 1721 raised $15.9 million), have reunited usurpers, notable players, and wealthy owners in an unlikely genealogical tree.

One of only ten surviving inlaid instruments by Antonio Stradivari, The “Sunrise” violin (1677). Taken from: Antonio Stradivari, Set 1, Volume 1, Page 96. Edited by Jost Thöne & Jan Röhrmann, Jost Thöne Verlag.

Early on, a certain mystique surrounded Stradivari and his work. His contemporaries could hardly explain the divine nature of the sounds he was able to extract from his instruments. The most extravagant theories circulated in those days, associating moon’s dewdrops, gold powder and the blood of frogs and virgins with the trademark cinnabar varnish that tainted them. But even before our dear Antonio began working, the violin had already gained a prominent role in the musical landscape. As early as in 1626, the French king Louis XIII created the first standardised orchestra, the famous “24 Violons du Roi” (The King’s 24 Violins). A few years later, in 1634, Mersenne called it the “King of Instruments.”

The birth of a rockstar & the rise of Italian music

Stradivari, based in Cremona, was just one of a brilliant batch of luthiers, including members of the Guarneri and Amati families, followed somewhat later by Domenico Montagnana and Giovanni Battista Guadagnini. All these artists were active in northern Italy, which was then at the forefront of modern developments in the construction of violins. Fostered by the partnership with composers and virtuoso players, they pushed forward a series of technical innovations that would build on the work of Nicolò Amati (grandson of Andrea Amati, founder of the modern violin) and Gasparo da Salò.

In 1693, Stradivari began experimenting with more extended patterns, which resulted in a deeper and fuller tone. Musicians were not insensitive to these improvements and seized this opportunity to explore the expression capabilities of the instrument. In 1700 Arcangelo Corelli published his highly influential Opus 5, a set of violin sonatas that would become the Baroque blueprint, irradiating this distinctive musical form well beyond the Alps. After him, other composers and players like Vivaldi, Locatelli, and Tartini further contributed to this literature, achieving cult status in Europe thanks to the fiery passagework and idiomatic language that characterised their instrumental pieces. It was the age of the violin virtuoso, the rise of an imaginary figure in popular culture with demonic and angelic powers in equal doses. The exuberant role played by the violin in sonatas and concerti would soon find its pendant in the vocal pyrotechnics of Italian operas. Both became symbols, in the instrumental and vocal fields respectively, of growing Italian influence in European music.

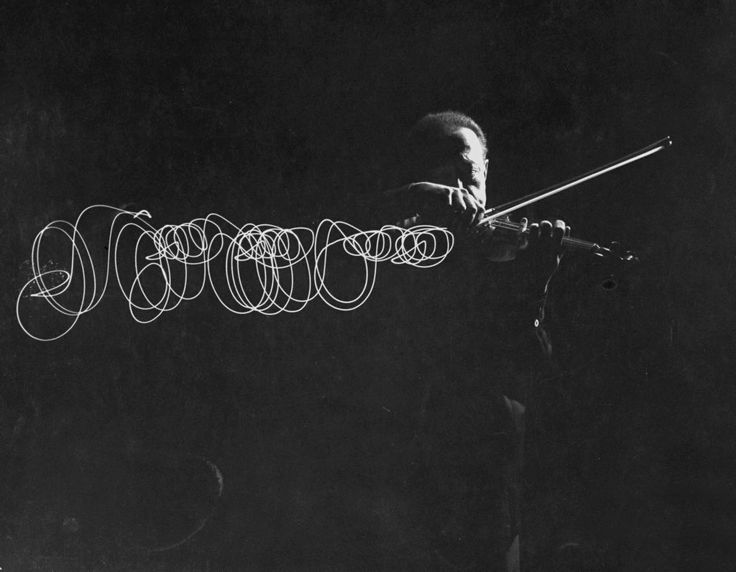

Violinist Jasha Heifetz is playing in Gjon Mili’s darkened studio. A small light was attached to his bow, revealing its movement during the performance—photo by Gjon Mili, Life Magazine, 1952.

Baroque opera in Italy and France: parting ways

Since the opening of the first public opera house in Venice in 1637, the Teatro San Cassiano, Italian opera had gained access to general audiences and escaped from the restricted courtly circles. Based on the inclusion of the da capo aria, which acted as a vehicle for the display of singers, helping to emphasise the emotions of characters (affetti), it became the lyrical standard in European theatres.

In France, where the Superintendant of Music Jean-Baptiste Lully dominated musical life, the Italian influence was smaller. Lully, a Tuscan by birth, laid the grounds for a distinctively French model of opera, based on the power of textual declamation. Lully’s operas were supported by slightly melodic recitatives and clear harmonic lines that facilitated the comprehension of the words. In 1672 he obtained from Louis XIV a privilege that ensured him a monopoly of opera representation, which would allow him to create the French counterpart of Italian opera, and implant this template nationwide. The tragédie lyrique, the name for this operatic form, was a type of musical drama inspired by the French classical theatre (Lully frequently collaborated with Molière, Corneille, and Quinault) and spiced up by dance movements drawn from the traditional French suite.

This form was developed from its precursor, the ballet à entrée, which consisted of four acts, each having a plot and punctuated by many character entrances and dance numbers. Lully also collaborated with Molière in the creation of the comédie ballet, which would blend dance numbers and songs into a cohesive unity, fully integrated with the action. Going one step beyond, he finally created the tragédie lyrique, which featured a prologue and five acts, usually heralded by a grand overture. The recitatives (spoken parts that sustained the action) sought to emulate the speech inflections of the French language and were a prominent rhetorical element in the drama. They were occasionally interrupted by choruses and dances. Politically used as a means of glorifying the Sun King, this model was followed by French composers even after Lully’s death in 1687.

The French opera of the Ancien Régime: political propaganda?

Nevertheless, this encrypted form of political proselytism had to be suitably disguised: in syntony with Descartes’ Méditations, the marked rationalism that permeated French thinking in XVIIth century and its sceptic approach to appearances did not authorise an open cult of vanity. For instance, in the opera Phaéton (1683), Jupiter restores the world’s order and promises to his people a new Golden Age. For the attentive viewer, it was not difficult to establish a link with Louis XIV, who had recently brought peace to Europe, emerging as a powerful continental ruler. This opera premiered in the newly built palace of Versailles, at the zenith of France’s ascendancy in European affairs.

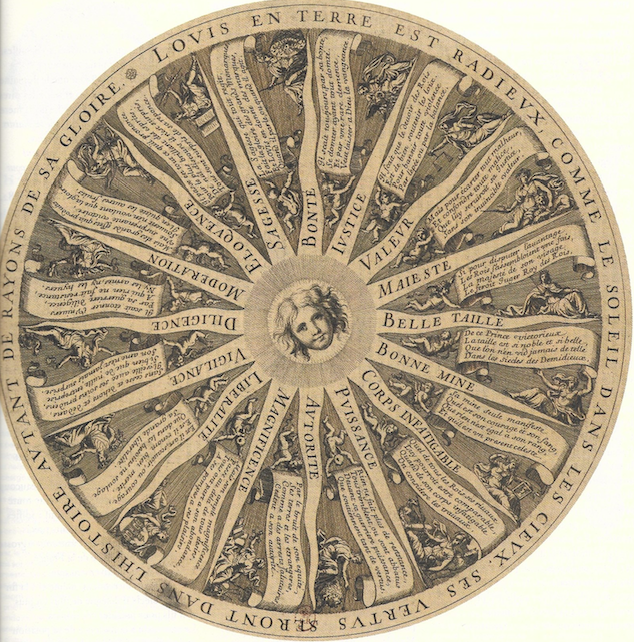

Hand-screen used as a shade against the heat of a fireplace, representing the virtues of the Sun King, 1684.

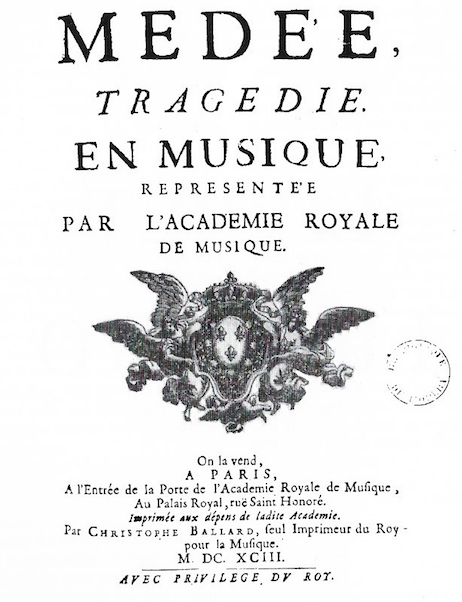

Reason, logic, and order were central to XVIIth century France and the use of opera as a vehicle for strong passions, as in the Italian model, did not have many adepts. One of the composers who most suffered Lully’s protectionism was Marc-Antoine Charpentier. Equipped with his knowledge of Italian oratorio, acquired during his Roman tenure with Carissimi, he introduced elements of the Italian style into his music. With restricted access to royal circles, many of his vocal works were commissioned by a wealthy patron with a fondness for Italian music: Mademoiselle de Guise. His tragédie lyrique Medée (1693) is the only opera he composed for the Académie Royale de Musique, the institution controlled by Lully. Fittingly, the first representation took place six years after the passing of the composer who had amassed enormous power and influence in the French musical scene.

Frontispiece of the tragédie-lyrique Medée (1693), by Marc-Antoine Charpentier.

The French resistance & the twilight of Louis XIV

In the years following Lully’s demise, although things relaxed a bit for Italophiles, some musicians remained staunch followers of Lully’s party. Among those who championed the French art against the rising influence of Italian music was Marin Marais, perhaps the most celebrated French viol player. He went to the extreme of forbidding his students to play Italian sonatas! But this was probably an overzealous reaction in his effort to protect his beloved bass viol from the looming menace of the Italian violin repertoire.

Marin Marais (1656-1728). French composer and bass viol player.

The bass viol or basse de viole in French (viola da gamba, in Italian) had achieved a prominent place in the French instrumental music from the XVIIth century. Often seen as the only instrument that could successfully rival with the human voice, which for many Baroque musicians was the golden standard, it was the dedicatee of collections that included evocative pieces, dance-like tunes and the elegiac tombeaux for the departed.

This repertoire encapsulates many of the features of French Baroque music of this period: it is sombre, elegant and introspective. In the 1690s the literature for French viol would get a full-bodied character, heavy in tannins. Twilight was impending: the ailing Sun King ruled an indebted country, and lavish public spectacles were no longer necessary to sustain his reputation. The music from this period is delicate and fragile, announcing the end of an old order. This intimate repertoire required small instrumental ensembles where the bass viol contributed its noble character.

Les goûts réunis: a synthesis of both schools

Meanwhile, in Paris, the fate of the violin sonata seemed to be in safe hands. According to Sébastien de Brossard, in the 1690s “every composer in Paris was madly writing sonatas in the Italian manner.” In the years that followed, many French musicians tried to create a synthesis of both styles. In the Parnassus of his collection Les Goûts réunis (1724), François Couperin reserved a preeminent place for Corelli and Lully, dedicating an Apothéose to each of them. André Campra successfully combined “la délicatesse de la musique française et la vivacité de la musique italienne” (the refinement of French music and the liveliness of the Italian music).

In the 1730s, the literature for viol entered a shadow cone and aroused a violent reaction from its supporters, who powerlessly observed the growing tide of Italian music. In the pamphlet Défense de la basse de viole contre les entreprises du violon et les prétentions du violoncelle (Defense of the bass viol against the undertakings of the violin and the pretentions of the cello), Hubert Le Blanc described an ominous scenario.

In his view, the viol would dispute the throne of the “Monarchie Universelle” (Universal Monarchy) with its formidable rivals: the violin, the harpsichord, and the cello. Between 1752 and 1754, this anti-Italian wave would continue with a venomous exchange of libels in the so-called Querelle des Bouffons. This dialectic confrontation took place between the defenders of the French opera («the King’s Corner» represented by Rameau) and the supporters of Italian opera («the Queen’s Corner» grouped around Rousseau).

Luckily enough the waters stilled, allowing French composers like Jean-Marie Leclair and Jean-Joseph de Mondonville to write great violin sonatas in the Italian manner and without any physical consequences. Today, les goûts réunis shine as brightly as ever, in the hands of young musicians specialised in the Baroque repertoire.

References

Baroque music. From Monteverdi to Händel. Nicholas Anderson. 1994, Thames & Hudson, London.

Miroirs de l’infini. Le jardin à la française et la métaphysique au XVIIe siècle. Allen S. Weiss, Editions du Seuil, 2011, Paris.

Diapason, nr. 637, July-August, 2015.